When we first met him, he was wearing a dark short-sleeved shirt and glasses, looking slightly serious. However, as we started talking, his gentlemanly and kind tone, coupled with the passion and smiles when discussing games, revealed the unique charm of a true gamer.

We began with why he left China. As a top graduate from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Xu joined Ubisoft Shanghai right after graduation and participated in developing the famous Tom Clancy series. In 2005, he was undoubtedly at the forefront of China’s gaming industry. Yet he wasn’t satisfied. Perhaps because Ubisoft Shanghai at the time was mostly involved in collaborative projects, he couldn’t access the cutting-edge of the gaming industry. Driven by curiosity, he chose to leave China for overseas.

When asked why he chose the UK, Xu frankly stated that the first job offer he received was from a British game company. Additionally, the UK’s immigration policy was relatively lenient at the time, so he ultimately decided to go there. He sighed, “Many choices in life aren’t made by you; life chooses for you.”

After arriving in the UK, he worked at several world-renowned game companies, including Sony, Disney, and Sega. In the past, overseas single-player game developers have long been role models for domestic game developers, who often wonder about their development processes. As a 3A game developer who left China and spent over a decade in the UK, he told us that the production processes for single-player games in China and the UK are actually not that different. Xu believes, “Whether domestically or internationally, the core philosophy of game development is to prove that a game is fun with the least cost.”

Regarding the most painful part of game development, he gave an unexpected answer: “When the first playable demo is ready.” Xu explained that after the first demo, you realize the game might not be as fun as imagined, and the art might not be as impressive. This is the stage where projects are most likely to be canceled, which is extremely heartbreaking.

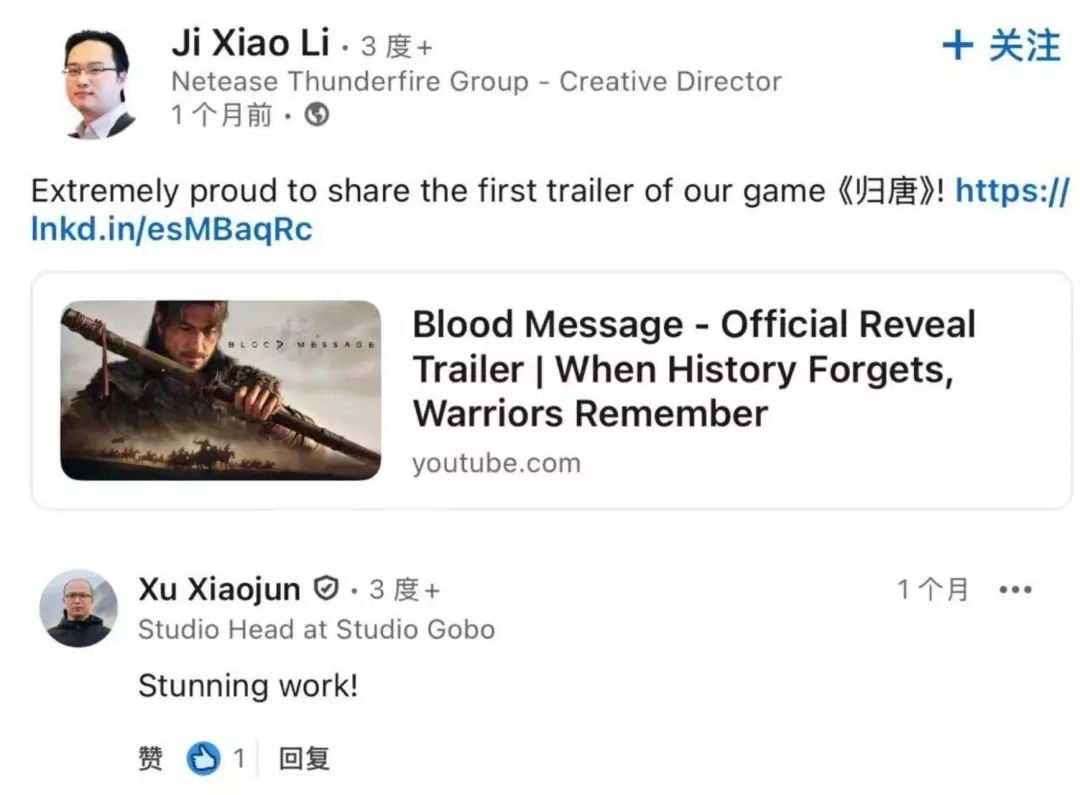

By chance, he joined Studio Gobo in 2012, a company founded just a year prior that focuses on supporting 3A game development and providing development services to large studios. During his time at Gobo, he led the team in collaborating with Tencent, Microsoft, Sony, Ubisoft, and other major game companies, assisting in developing popular titles such as Disney Infinity, Hogwarts Legacy, For Honor, and SYNCED Off-Planet.

In 2021, Xu officially took over as head of Studio Gobo, making it the longest he has stayed at any game company. “My initial decision to join Gobo wasn’t driven by career aspirations but by family reasons,” Xu added. “But what kept me at Gobo is finding like-minded colleagues who allow me to keep doing this work.”

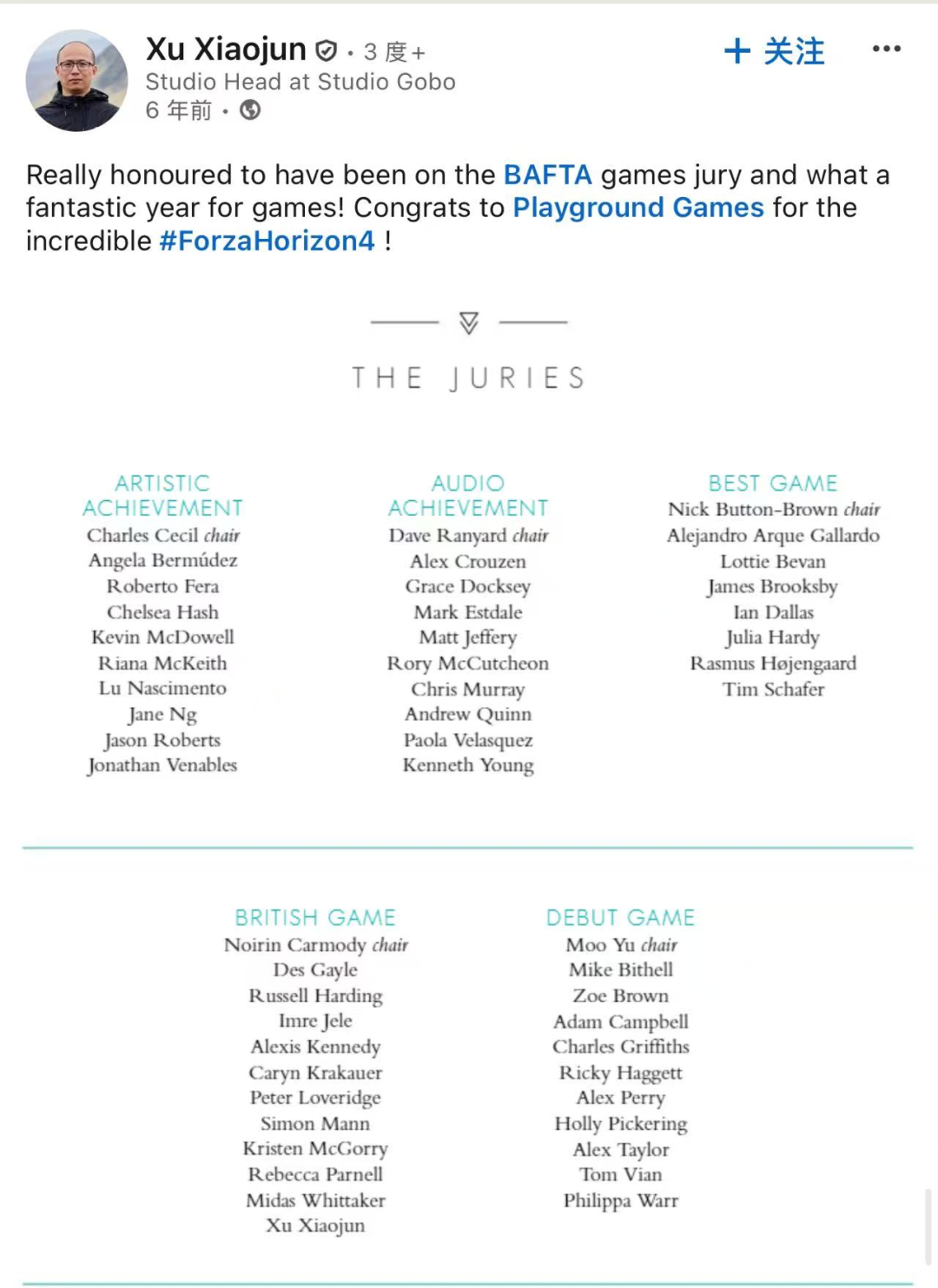

With growing industry experience, Xu became a jury member of the BAFTA Games Awards—one of the five major game awards—six years ago. We thus asked him a question that has puzzled both us and many players: “Why do BAFTA’s Game of the Year selections seem so ‘unconventional’ every year?”

“Each BAFTA award gathers industry experts and invites judges with diverse perspectives,” Xu replied. “Therefore, when evaluating a game’s quality, it doesn’t narrow its focus to a single aspect. Overall, I think BAFTA assesses games more comprehensively rather than setting absolute criteria for judgment.”

After over a decade in the UK, Xu believes the UK taught him to see things from others’ perspectives. He joked, “What frustrates Britons most is when someone blocks their way.” He emphasized that this has greatly helped his game design. Meanwhile, his work experience in China taught him that hard work pays off and that a serious attitude toward work—whether in study or career—is essential.

When asked about his views on the development of single-player game industries in China and the UK in recent years, Xu noted that for the domestic market, more people are making domestic 3A games, and the quality of these works is improving. For the UK market, he objectively pointed out that many major companies, including Microsoft and Sony, are laying off employees, while the commercial returns of 3A games are declining.

Currently, many laid-off British developers tend to create small-scale original games. In fact, in recent years, we have seen many impressive titles from small European teams, such as Expedition 33 from France, which has one of the highest ratings in recent years.

When asked about differences in collaboration between Chinese and overseas game companies, “cultural differences” were his top answer. Xu shared that foreign teams are highly individualistic, sometimes making management challenging, but they often bring novel ideas and perspectives and proactively propose solutions when development hits a snag. In contrast, domestic teams excel in teamwork and work ethic, though they sometimes joke about being “overly competitive.”

He emphasized that great game works require such perseverance to come to life.

Below is an edited version of the interview for readability:

From Ubisoft Shanghai to Studio Gobo in the UK

Jinghe: You first worked at Ubisoft Shanghai. Why did you later choose to go abroad?

Xu Xiaojun: Curiosity. At the time, Ubisoft Shanghai was a cooperative developer working with other Ubisoft studios. After working on Tom Clancy titles for two or three years, you feel you’re not seeing the cutting-edge, creative elements of the industry.

Of course, I was very junior back then and didn’t fully understand the industry. So I decided to go out and explore, to see how other studios operate. Honestly, my decision wasn’t fully thought out; I went to the UK with a simple, even naive belief.

Jinghe: From a global game development perspective, many people choose the US, Singapore, etc. Why did you choose the UK?

Xu Xiaojun: There was no special reason for choosing the UK. I sent my resume to companies worldwide and waited for offers. Options were limited since I wanted English-speaking countries—only the US, Australia, or the UK.

In 2007, the UK’s immigration policy was relatively lenient. If you got a job offer, getting a visa was easier. And a British company was the first to offer me a position. So, as I said, many life choices aren’t made by you; life chooses for you.

Jinghe: Do you think the development environments in China and the UK differ significantly?

Xu Xiaojun: From a development team perspective, the differences aren’t huge. Whether in China or abroad, people work in games because they love them and are passionate about the work.

Jinghe: Are there differences in the single-player game production process between China and the UK?

Xu Xiaojun: The production processes for single-player games in the UK and China are quite similar. Both aim to reduce uncertainties at each stage of development.

For example, at the start of a project, you might have a presentation, high-level concept documents, or even no code yet. But at each step, you want developers or investors to see the game’s potential. Later, you have playable builds so everyone understands what the game is, but initially, you have nothing.

So the core philosophy in both countries is: How do I prove my game is fun with the least cost? Whether through early documents, prototypes, or later playable versions.

Jinghe: In single-player game projects, from conception to launch, what’s the most challenging or painful stage?

Xu Xiaojun: The most vulnerable stage for cancellation is when the first playable demo is ready. Canceling a project after the first demo is heart-wrenching.

When brainstorming initial documents, everyone knows the success rate is low. But once actual production starts and the first demo is released, if it’s not as fun as expected, the game is likely canceled.

If the first demo shows potential, you can iterate to fix issues. But if it’s deemed unfun, the game has little hope.

Unlike China, where many art styles lean toward anime, foreign developers take bolder risks with art innovation.

Often, art style development runs parallel to the first playable demo. If the art style is deemed unappealing or unmarketable, it becomes another critical judgment point for the game’s viability.

Jinghe: After moving to the UK, you worked at Sony, Disney, Sega, etc. What differences did you notice between these companies, and which environment felt most comfortable?

Xu Xiaojun: The biggest difference is between Gobo and previous large publishers/developers. For a long time, I was responsible for profitability. Since Gobo is an independent studio, we sometimes take on any project to keep the team afloat.

In studios owned by large developers, many projects are already greenlit. Your task is to work on a specific project, and you might have more creative freedom thanks to ample company resources.

For example, at Creative Assembly, we developed a Total War tablet game—risky since Total War is a large-scale PC franchise. But the company’s size allowed it to support and afford such experimental projects.

In a smaller company like Studio Gobo, overinvesting in original projects could lead to failure, even inability to pay salaries, so there’s more business pressure.

In terms of stability, large companies definitely felt more secure. But with recent industry trends, it’s hard to say which is better. Personally, Studio Gobo has more survival pressure, especially from a leadership perspective.

Jinghe: How do you evaluate your decision to move to the UK, and what has the experience brought you?

Xu Xiaojun: The UK taught me a lot. China, during my growth, taught me that hard work pays off and that a serious attitude toward work—whether studying or working—is essential. It’s not about overtime hours but dedication. The UK taught me to see things from others’ perspectives.

We joke that Britons hate it most when someone blocks their path. They say “sorry” a lot because their values emphasize not inconveniencing others. This mindset helps them understand others’ viewpoints, which taught me to think from players’ and colleagues’ perspectives.

In game design, you need to convince programmers and artists that your design is sound. Only by empathizing with others can you effectively persuade your team. That’s what the UK gave me.

Work and Life at Studio Gobo

Jinghe: Why did you join Studio Gobo, and what attracted you to it?

Xu Xiaojun: Honestly, my decision to leave Creative Assembly for Gobo was a bit embarrassing—it was because it was closer to home. My daughter had just been born, and I needed more time for family.

But staying for 14 years is because of the team; we share common goals. If you asked me now where I’d go if I left Gobo, I’d say what matters most is who you work with to develop games, not the studio’s or game’s reputation.

Working with 20-50 like-minded people is what attracts me at this career stage. Though I joined Gobo for non-career reasons, I stayed because I found colleagues who let me keep doing what I love.

Jinghe: Studio Gobo is a game company focused on assisting in the development of 3A games and providing development support services to large studios. Compared with single-player products like Disney Infinity, Hogwarts Legacy, and Cyberpunk 2077, what differences do you see in the development processes or pipelines when assisting in the production of GaaS-oriented games like SYNCED Off- Planet?

Xu Xiaojun: I think people may have different opinions on this. For us, when it comes to GaaS-oriented games, the core theme and design of the game are basically clear when we join the project. The game may have already been launched, and we are co-developing parts of its first or second season content.

There’s little room for innovation in the core game, as the “building” is already built; we’re just adding “rooms.” This reduces team motivation.

However, original, non-GaaS (buy-to-play) games carry higher risks. As mentioned, your ideas or gameplay might not work, derailing the project. GaaS games avoid this pain since the template is set.

In terms of iteration, buy-to-play games require more iterations, while GaaS games use player feedback to quickly adjust future updates.

Jinghe: LEGO Horizon Adventures is one of our recently successful games. In the production of this product, were there any differences in our creative concepts compared to the games we usually make?

Xu Xiaojun: Actually, before this game, there had already been many LEGO single-player games. When we started this project, we noticed that many previous LEGO single-player games were adapted from movies. Therefore, in terms of game innovation, they focused more on trying to recreate the plots and shots of the movies as much as possible.

However, our game is adapted from Sony’s Horizon series, so we don’t have that advantage. Because if players want to experience the original work, they can just play the original Horizon games directly. Our starting point was more about how to adapt the LEGO element. In the end, we chose to take a sandbox approach rather than recreating the game scenes in a 1:1 ratio in our game.

I think the initial creative intention was more rooted in LEGO’s own values. They hope that when users get a box of LEGO bricks, they won’t just build according to the instructions. Instead, after finishing the build, there will still be a pile of LEGO bricks left. This ultimately inspired us to promote such a sandbox gameplay concept.

Jinghe: You’ve led teams collaborating with Tencent, Microsoft, Sony, Ubisoft, etc. What differences have you noticed between Chinese and overseas companies in collaboration?

Xu Xiaojun: Cultural differences exist. Domestic teams excel in teamwork and work ethic—we even joke about their “intense competition.” From a foreign perspective, this perseverance is inspiring, as long-term dedication is rare overseas. Yet great works require such persistence.

Foreign teams are more individualistic, making management harder, but they bring unique ideas and perspectives. When facing development challenges, everyone—from leadership to junior staff—voices solutions. Both approaches have pros and cons, but cultural differences are clear.

Jinghe: As a support studio, you collaborate with people from many countries, facing issues like time zones and cultural gaps. For example, some find Chinese staff “overly competitive,” while others say overseas staff are hard to reach. What differences do you see in collaborating with Chinese vs. foreign developers?

Xu Xiaojun: Fundamentally, developers in both regions are similar. Overseas, some work hard, some slack off. What matters is your output.

Overseas staff value work-life balance, but during their 8-hour workday, they stay focused with no distractions or personal tasks. There are exceptions, but such behavior is penalized. So it’s not that foreign developers are “more disciplined.”

They protect personal time, but work hours are fully dedicated to the company. As long as output meets standards, it’s a sustainable work model.

Jinghe: How do you view China’s “intense competition” culture, and how do you ensure project completion while keeping staff comfortable?

Xu Xiaojun: Overseas teams also work overtime and face busyness. Domestic teams may be more accustomed to overtime, but it’s not unique.

At Gobo, honesty with staff is crucial. If the company faces bad news—lost projects, poor business—we share it openly.

When choosing projects, we explain our decision-making: e.g., “This project is profitable” or “We need it despite weak creativity due to financial constraints.”

This builds trust. When deadlines are tight, the team feels we’re in it together. With close ties between management and staff, they trust our decisions.

Thus, when we ask for extra effort in final months, overtime is voluntary. No one is forced to stay once tasks are done.

Jinghe: Have you faced conflicts between Chinese partners’ schedules and UK holidays like Christmas? How do you handle it?

Xu Xiaojun: We have indeed encountered such situations. Including the project we are working on now, it is a GaaS project. As a GaaS project, of course, you cannot fully test everything. Additionally, according to the contract, the game may have version updates on Thursdays or Fridays. If a major bug is found on Saturday, what should we do? You can’t wait for two or three days because the version is being played by players all over the world.

In such cases, we will arrange for employees to work overtime. Some people will say that working on weekends violates their rest time. But we usually ensure fairness: if you sit at work all day on Saturday and have nothing to do, we will give you that day back. You can choose a weekday to take a rest when the project workload is lighter.

If there is a real problem on the weekend and you spend a lot of time fixing it, we will give you two days off for one day of work. Moreover, we will explain such rules to employees frankly from the beginning, and they apply equally to everyone. If it is your responsibility and you need to come to work overtime, everyone is more willing to accept it, and fairness is the key consideration here.

Also, when collaborating with domestic partners, we don’t really celebrate Christmas, but Christmas in the UK is just like the Spring Festival for us. Therefore, I generally hope to avoid making Christmas a critical deadline. Usually, the December version is basically completed in early December.

However, if there is really an important version event, we will inform our employees in advance to let them prepare. I think foreign partners are quite reasonable, and the key here is to adhere to the principle of fair dealing.

Contrasting Game Industries in China and the UK

Jinghe: In recent years, what changes have you seen in China’s 3A game development? What areas still need improvement compared to traditional overseas studios?

Xu Xiaojun: More people are making 3A games, and the quality is improving.

As a developer and player, this diversifies China’s game output. Previously, focus was on mobile games, but I’m not a big mobile gamer—I prefer single-player titles.

Many Chinese traditional themes are untouched by Western developers. Japanese or Korean studios might explore them, but Western teams rarely delve into Eastern themes.

As a player, having more quality options is praiseworthy. Making 3A games is extremely hard, so seeing them completed is remarkable. I sincerely believe we should encourage each other to keep improving.

It’s truly heartening to see so many people in China making 3A single-player games.

Jinghe: What’s your view on the UK game industry’s development in recent years?

Xu Xiaojun: In terms of trends, we have seen the industry go through a lot of layoffs recently. Many major companies, including Microsoft and Sony, have reduced their number of employees. At the same time, the commercial return rate of 3A games is not good.

Even against this backdrop, I still know that many British developers—whether they have been laid off or have been with major companies for a long time—have a strong desire to create smaller-scale games with more unique and original content. They don’t aim to achieve the perfection of 3A games; instead, they incorporate some small innovations into their work.

Therefore, I think nowadays, people can see that many small game developers are often bold enough to pursue innovation and originality.

Jinghe: Regarding recent layoffs, what do Chinese and British companies prioritize when hiring game designers? Are there differences, such as China’s reluctance to hire over 35s?

Xu Xiaojun: In the UK, age doesn’t actually have any impact.

Moreover, the original intentions behind hiring experienced professionals and graduates are different. When hiring experienced people, you hope to gain their industry experience. Therefore, those over 35 or with 15 to 20 years of experience in the industry are also highly regarded. However, when hiring graduates, it’s more about whether they align with your company’s values. You want the recruited graduates to collaborate with the team in line with these values, so both are extremely valuable.

From a game designer’s perspective, when I was applying for jobs, technical skills were very important. Being able to directly implement functions in the game engine, write scripts, or program—even for designers—these technical abilities are very helpful.

Abroad, these technical skills are certainly important, but they may value more qualities like curiosity, the ability to keep learning, or the capacity to see things from others’ perspectives. Foreign employers pay more attention to such non-technical skills.

However, this is also determined by the domestic situation, as there are many applicants. When you have a large number of candidates, how do you fairly select the outstanding ones? Then, whether intentionally or unintentionally, technical skills will be valued.

Jinghe: What’s your view on the current mobile game markets in China and the UK?

Xu Xiaojun: I think domestic mobile games are used in more diverse ways than foreign ones. You can find many in-depth games on mobile phones in China, which is relatively rare abroad.

Many domestic games are accessible to foreign players through various channels, but foreign mobile game players mostly play casual games that take five to ten minutes. It’s quite rare for them to play in-depth games on mobile devices.

Players interested in in-depth games usually choose single-player games or PC games. If they want to play for half an hour or an hour at a stretch, they prefer to do so on single-player platforms or PCs.

But in China, people are very accepting of mobile phones for gaming. It’s very common to play games on mobile phones for half an hour or an hour. This is not common abroad, where mobile game players still prefer short-term games. Of course, there are also players abroad who enjoy in-depth mobile games, but their proportion is much smaller than in China.

Jinghe: As a jury member of BAFTA, one of the five major awards in the gaming industry, what differences do you think exist between China and the UK in evaluating a game, and how do their evaluation systems differ?

Xu Xiaojun: For BAFTA, its review mechanism involves gathering some industry experts for each award. However, BAFTA deliberately invites judges with different perspectives. Therefore, when evaluating a game’s quality, it doesn’t focus narrowly on a single aspect.

For example, when assessing art, some judges may pay more attention to whether the artistic techniques are excellent. Another judge may focus on whether the art style is outstanding. Still others may look at whether the visual realism is exceptional.

When evaluating innovation, some may focus on hardware innovation, while others emphasize innovation in gameplay. I’m not sure about other awards, but BAFTA is a very inclusive organization. It consciously incorporates diverse perspectives. So it doesn’t solely focus on commercial success; it also intentionally expands the range of candidate games. Compared with previous years, the pool of candidate games has grown larger in recent years, allowing judges to see more games.

Overall, I think BAFTA evaluates games in a more comprehensive way rather than setting absolute criteria. For instance, it doesn’t stipulate how many frames per second a game must have or how many polygons it must render. It avoids setting rigid parameters and is more willing to openly accept the subjective perspectives of experts.

Jinghe: As a veteran who has been developing 3A single-player games in the UK for over a decade, what experiences can you share with domestic small and medium-sized teams developing single-player games?

Xu Xiaojun: I don’t think I can call it “experience”; they are just my own thoughts. Even in 3A game development now, as development costs keep rising and games become more expensive, players’ spending hasn’t increased substantially.

Therefore, for the entire industry, we must spend money more wisely. Especially from a “2A” perspective, you can’t match the scale of 3A games. Many times, you need to ask yourself: What can I skip? What can I confidently say I don’t need because my selling point lies elsewhere?

Many people who make single-player games do so with a romantic passion, wanting to create high-quality products. But “quality” doesn’t mean making every aspect of the game extremely costly. You must wisely decide what you want and what you don’t want.

It’s similar to life. If you have a limited budget for decorating a house, you need to figure out what’s important to you. You have to ask yourself what you can skip, and skip it willingly.

As 3A development costs continue to rise, this also applies to many 3A developers. Not everyone has what is now called “4A-level” funding. So, what aspects that other 4A games include can I skip because my game doesn’t rely on them for its appeal?

Jinghe: If some domestic developers or studios want to go to the UK to make games, what advantages do you think they would have, and what advice do you have for them?

Xu Xiaojun: I don’t think there are any specific, practical suggestions. One idea that applies to anyone going abroad to make games is to approach it with an open mind and first seek integration in culture and values. Because each country has many different traditions and values.

In the UK, the entrepreneurial environment itself is very good; you can set up a new company quickly, and there are very favorable tax policies for game development. However, this doesn’t guarantee success. If a purely Chinese team wants to move entirely to the UK, I think the practical operation would be quite difficult.

A more feasible approach is for a Chinese-led team to establish a game company in the UK. I think this is very viable. But it’s important to communicate and coordinate well with employees; the obstacle is not just language but, more importantly, cultural understanding.

We need to continuously help British colleagues understand Chinese culture, and also embrace an open mind to understand local British culture. I think only in this way can everyone have meaningful exchanges.

本文系作者Zhang LongXi授权竞核发表,并经竞核编辑,转载请注明出处、作者和本文链接。想和千万竞核用户分享你的新奇观点和发现,点击这里投稿。